derekcohen

Member

- Joined

- Jun 22, 2008

- Messages

- 922

I'd like to throw this one out for discussion.

This is table I have just replaced ...

The plan is to restore it and give it to my son and daughter-in-law.

My wife and I purchased it shortly after we married, some 42 years ago now. At that time it was said to be 150 years old. The table is a kitchen table typical of those built in farming communities in the Eastern Cape area of South Africa. The timber is Yellow Wood, a much prized and now rare light softwood, found only in Southern Africa and South America, and Stinkwood, which is a hardwood similar to Teak.

When we purchased the table, it had undergone a "restoration" by a local furniture maker, amateur I suspect. It held up well, but over the past five years began to develop cracks and splits. I aim to repair these. So for discussion is the extent of the finishing, the repair of the splits, and modifying the way the table top is attached. Glue(s) to use? Photos below ...

Splits in the table top ...

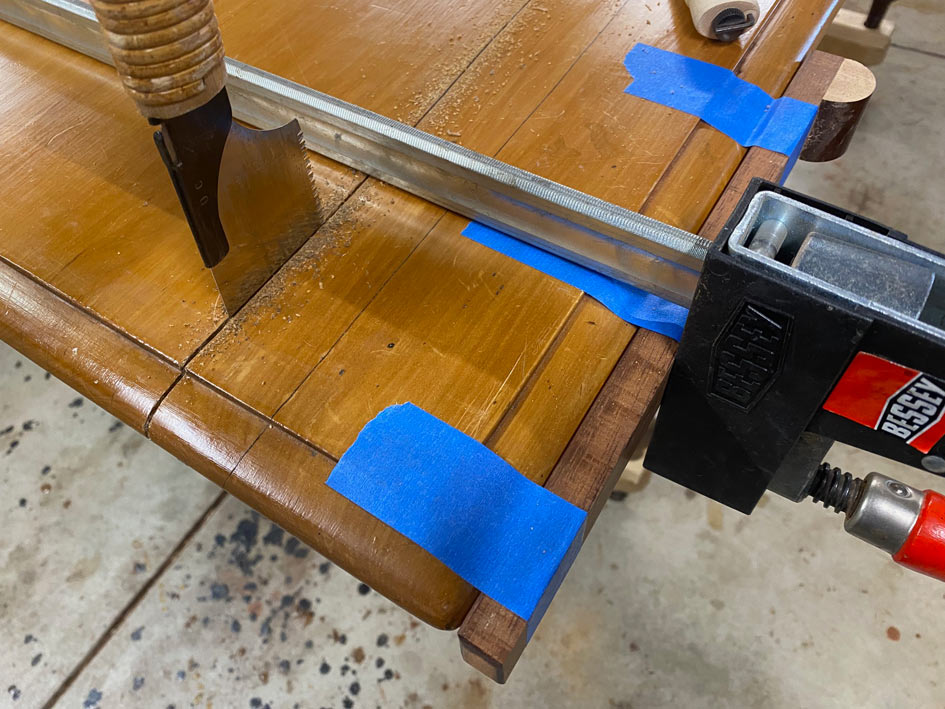

Slip at one leg joint ...

The top is attached with pocket screws (not the Kreg type!) made with a brace and bit. These do not build with wood movement in mind!

Further, the bracing of the top looks like a modern add-on and, again, prevents movement ...

The tops of the legs are all chamfered to avoid contact with the table top ...

These are the screws that came out ..

Thoughts?

Regards from Perth

Derek

This is table I have just replaced ...

The plan is to restore it and give it to my son and daughter-in-law.

My wife and I purchased it shortly after we married, some 42 years ago now. At that time it was said to be 150 years old. The table is a kitchen table typical of those built in farming communities in the Eastern Cape area of South Africa. The timber is Yellow Wood, a much prized and now rare light softwood, found only in Southern Africa and South America, and Stinkwood, which is a hardwood similar to Teak.

When we purchased the table, it had undergone a "restoration" by a local furniture maker, amateur I suspect. It held up well, but over the past five years began to develop cracks and splits. I aim to repair these. So for discussion is the extent of the finishing, the repair of the splits, and modifying the way the table top is attached. Glue(s) to use? Photos below ...

Splits in the table top ...

Slip at one leg joint ...

The top is attached with pocket screws (not the Kreg type!) made with a brace and bit. These do not build with wood movement in mind!

Further, the bracing of the top looks like a modern add-on and, again, prevents movement ...

The tops of the legs are all chamfered to avoid contact with the table top ...

These are the screws that came out ..

Thoughts?

Regards from Perth

Derek

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/100504591-bbffee6e0ac34be798f3d475c995eb49.jpg)