derekcohen

Member

- Joined

- Jun 22, 2008

- Messages

- 1,043

This article is for all who wish to make a dovetail saw, but feel intimidated, and for all who need to sharpen their dovetail saws, which is everyone. Sooner or later, even the most expensive saw will need to be re-sharpened. Even touched up every now-and-then.

We have many, many threads on sharpening plane blades and chisels, but not many on sharpening backsaws. Well, I am not an expert on making backsaws, having done about a dozen, although I have been sharpening my saws for about 15 years. Still, I consider myself a novice, which places me in touch with all others who feel a little overwhelmed by the process. I have developed a few strategies to make it all easier, and these I want to pass on. It would be great if those who are more experienced are prepared to comment, and add their advice.

This is a long post, as there are so many photos, and so I have divided it into two sections: firstly, building the dovetail saw; secondly, sharpening and setting the teeth.

Building a Dovetail Saw

There are four components in a dovetail saw: the plate, the brass back, saw nuts, and the handle.

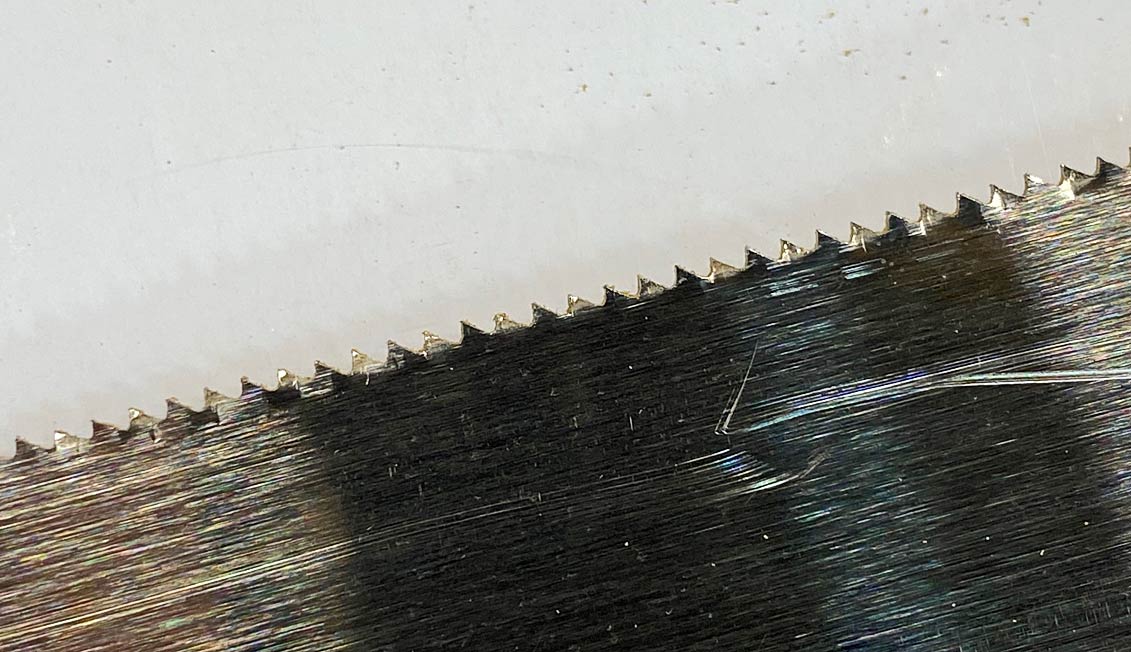

In this case, the 9” plate and brass back came from Isaac Smith at Blackburn Tools. The motivation for making this saw is that I was curious about a thin-plate dovetail saw. The supplied plate is 0.015” thick, and comes machine filed (i.e. not sharpened) at 16 ppi with 5 degrees of rake.

This will be a tapered plate, with 1 5/16" at the toe and 1 1/2" at the heel. Total cost $39 USD.

The saw nuts I already had, having purchased a bunch over a decade ago from Mike Wenzloff. This is the last of them.

The wood for the handle is an offcut in gorgeous fiddleback Jarrah.

You are also going to need to drill the saw plate, and Isaac also stocks solid carbide spade drill bits. Photo in a little while.

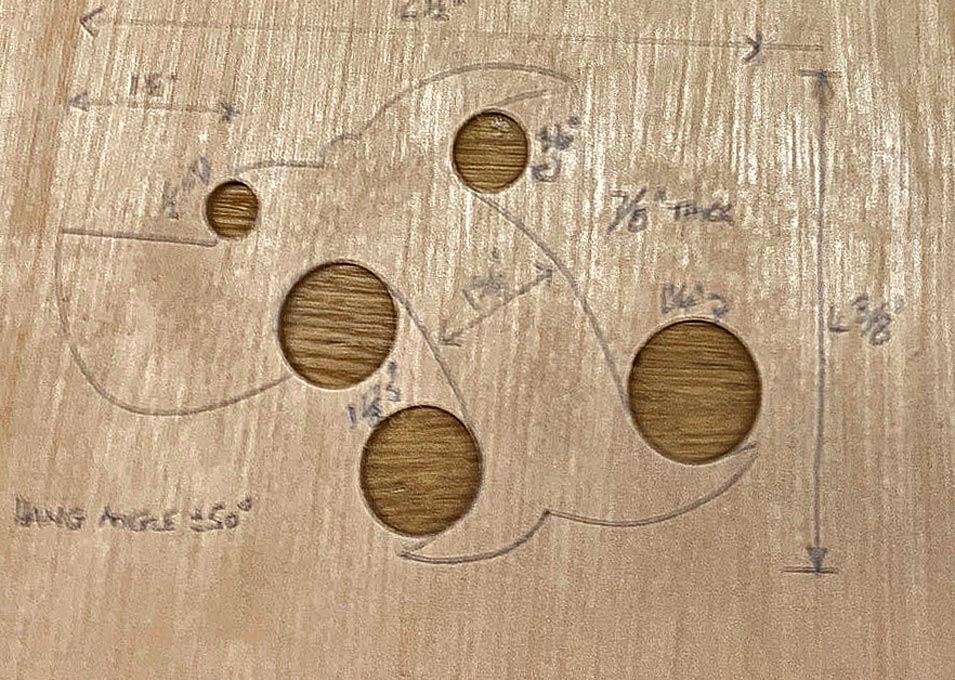

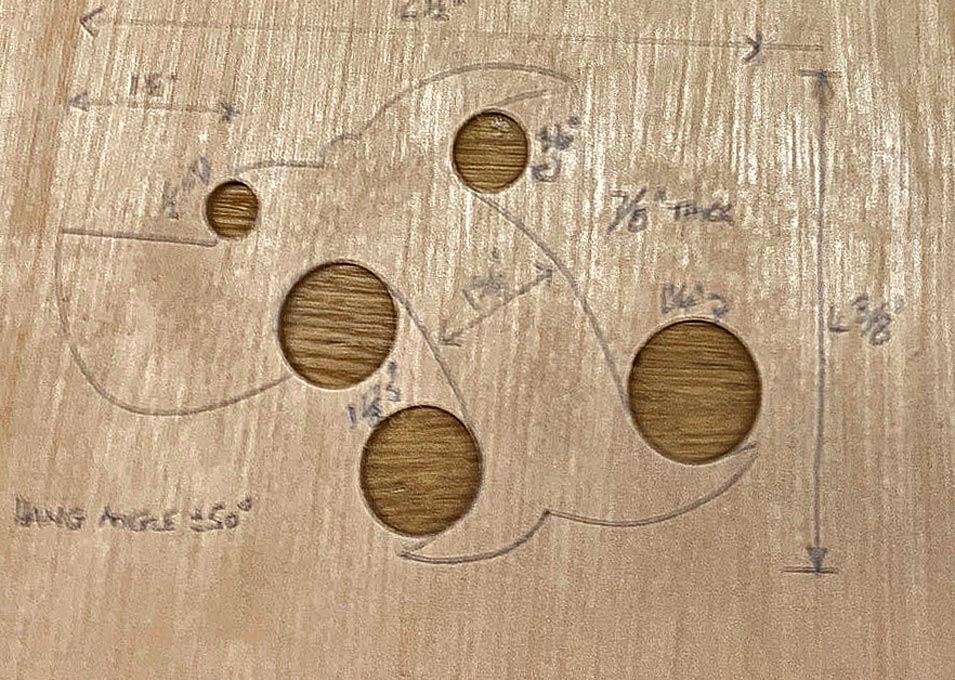

Isaac’s site freely offers a number of templates of handles. I chose to make my own, based on a vintage Groves dovetail saw.

Below is the template I made, showing the cut outs to aid in sawing the outline. Not the clearest photo.

I am going to assume that everyone can get as far as sawing the outline. The first tip I will give is that it is vital that square is maintained throughout …

Secondly, mark guide lines to work to …

Only begin to fare in the curves when the final outline is completed …

As you reach the end of shaping, the mortice for the brass back needs to be cut before the slot for the blade. Mark out the boundary lines, and drill out the centre to depth. Leave a little to pare away …

Getting the blade slot square and centred is vital to keeping the plate straight. An out-of-square slot will the thin plate to its shape, and leave a curved tooth line.

In order that the slot remains square and vertical, I made a simple jig to guide the saw used to make the slot. Incidentally, the saw used – one which cut a tight kerf – was a Japanese Z-saw …

The order of drilling the holes for the saw nuts is to start with a pilot hole …

… followed by countersinking the heads and split nuts …

Now you are ready to mark the positions on the saw plate …

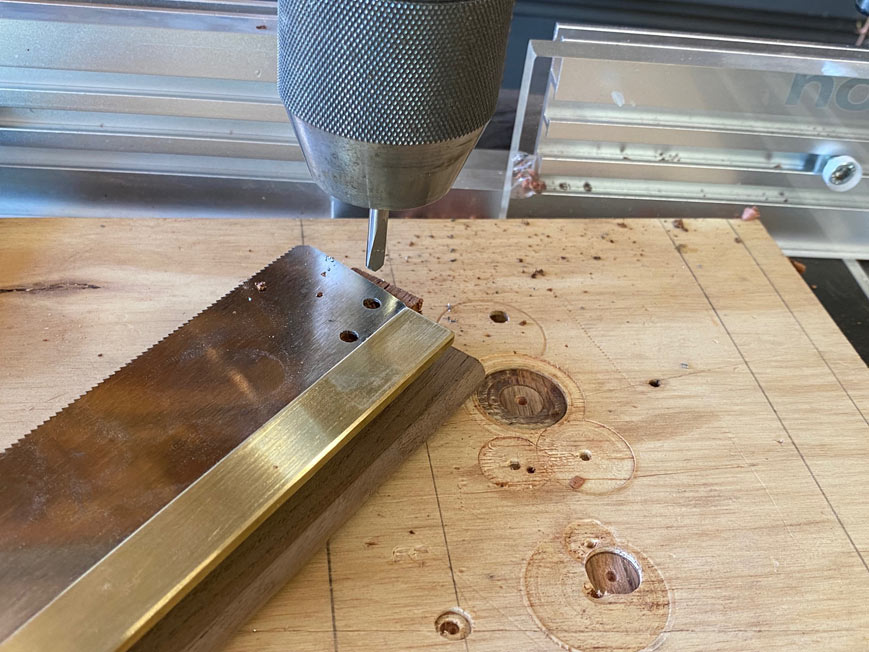

… and drill the holes with the carbide spade bit

Note that the drilling is done prior to any shaping. This is to maintain the maximum registration surface.

I did not take photos of gluing the plate into the brass back. This is too easy – just use Locktite. The brass back will need to have the edges eased or chamfered with a file or sander, and then polished.

End of Part One.

Regards from Perth

Derek

We have many, many threads on sharpening plane blades and chisels, but not many on sharpening backsaws. Well, I am not an expert on making backsaws, having done about a dozen, although I have been sharpening my saws for about 15 years. Still, I consider myself a novice, which places me in touch with all others who feel a little overwhelmed by the process. I have developed a few strategies to make it all easier, and these I want to pass on. It would be great if those who are more experienced are prepared to comment, and add their advice.

This is a long post, as there are so many photos, and so I have divided it into two sections: firstly, building the dovetail saw; secondly, sharpening and setting the teeth.

Building a Dovetail Saw

There are four components in a dovetail saw: the plate, the brass back, saw nuts, and the handle.

In this case, the 9” plate and brass back came from Isaac Smith at Blackburn Tools. The motivation for making this saw is that I was curious about a thin-plate dovetail saw. The supplied plate is 0.015” thick, and comes machine filed (i.e. not sharpened) at 16 ppi with 5 degrees of rake.

This will be a tapered plate, with 1 5/16" at the toe and 1 1/2" at the heel. Total cost $39 USD.

The saw nuts I already had, having purchased a bunch over a decade ago from Mike Wenzloff. This is the last of them.

The wood for the handle is an offcut in gorgeous fiddleback Jarrah.

You are also going to need to drill the saw plate, and Isaac also stocks solid carbide spade drill bits. Photo in a little while.

Isaac’s site freely offers a number of templates of handles. I chose to make my own, based on a vintage Groves dovetail saw.

Below is the template I made, showing the cut outs to aid in sawing the outline. Not the clearest photo.

I am going to assume that everyone can get as far as sawing the outline. The first tip I will give is that it is vital that square is maintained throughout …

Secondly, mark guide lines to work to …

Only begin to fare in the curves when the final outline is completed …

As you reach the end of shaping, the mortice for the brass back needs to be cut before the slot for the blade. Mark out the boundary lines, and drill out the centre to depth. Leave a little to pare away …

Getting the blade slot square and centred is vital to keeping the plate straight. An out-of-square slot will the thin plate to its shape, and leave a curved tooth line.

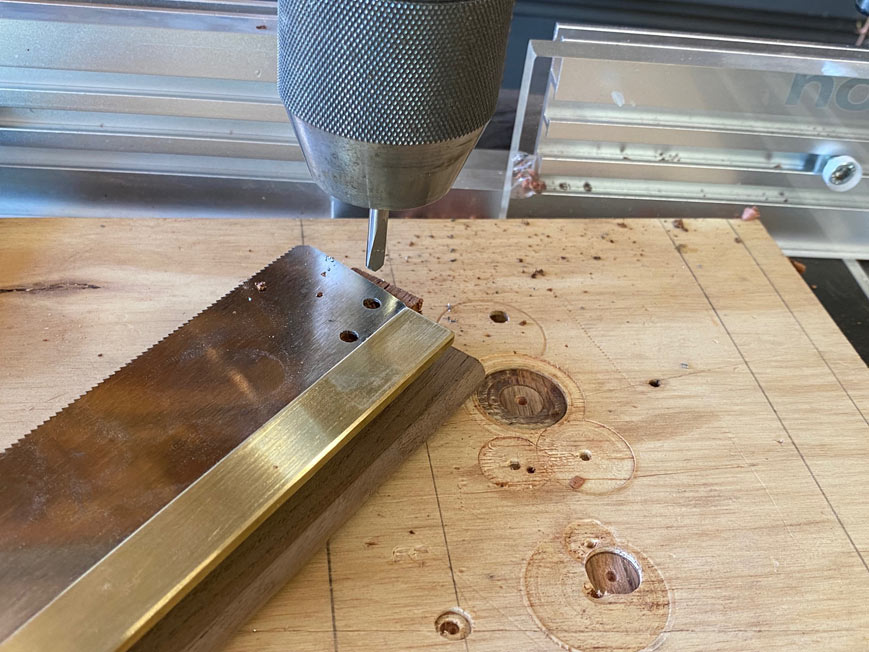

In order that the slot remains square and vertical, I made a simple jig to guide the saw used to make the slot. Incidentally, the saw used – one which cut a tight kerf – was a Japanese Z-saw …

The order of drilling the holes for the saw nuts is to start with a pilot hole …

… followed by countersinking the heads and split nuts …

Now you are ready to mark the positions on the saw plate …

… and drill the holes with the carbide spade bit

Note that the drilling is done prior to any shaping. This is to maintain the maximum registration surface.

I did not take photos of gluing the plate into the brass back. This is too easy – just use Locktite. The brass back will need to have the edges eased or chamfered with a file or sander, and then polished.

End of Part One.

Regards from Perth

Derek