derekcohen

Member

- Joined

- Jun 22, 2008

- Messages

- 956

I thought that the build might begin with preparing the panels, since there has been some interest in the past shown in the shorter Hammer K3 sliders. Mine has a 49" long slider and a 31" wide table for the rip fence.

The build is an entry hall table for a wedding present for a niece. Her choice was this mid century modern piece, which will be the basis for the build. My job is to re-invent it somewhat.

She wants Jarrah, and I have managed to find something spectacular ... a subtle fiddleback (curly) set of boards that will make a book match (as they are only about 9" wide each).

Most imagine that the value of a slider lies with cross-cutting. It certainly is so. However it is the rip using the slider - rather than the rip fence - which is so amazing.

One side of each board was to be ripped on the slider, before being jointed and resawn. Ripping on the slider is such an advantage with life edges. No jigs required. No rip fence to slide against. Just clamp the board on the slider, and run it past the saw blade. The long sliders can complete the rip in one quick pass. It occurred to me that I should take a few photos of ripping to width since the boards are longer than the slider.

Here you can see that it comes up short ...

In actuality, with the blade raised fully, there is a cut of nearly 54" ...

The solution is to use a combination square to register the position of the side of the board at the front, and then slide the board forward and reposition it ...

... and repeat at the rear ...

The result is a pretty good edge, one that is cleaned up on the jointer in 1 or 2 passes, and then ready for resawing ...

This is the glued panel. It is long enough to make a waterfall two sides and top section (still oversize) ...

The following photo shows the lower section at the rear. What I wanted to show is the way boards are stored. Since I shall not get back to this build until next weekend, all boards are stickered and clamped using steel square sections.

The steel sections are inexpensive galvanised mild steel. These are covered in vinyl duct tape to prevent any marks on the wood and ease in removing glue ...

Done for the day ...

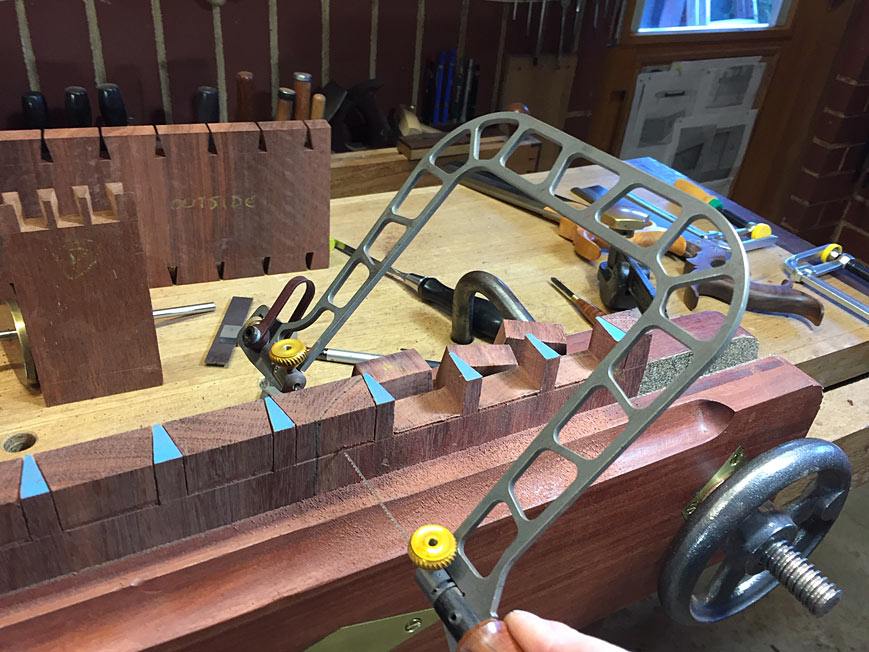

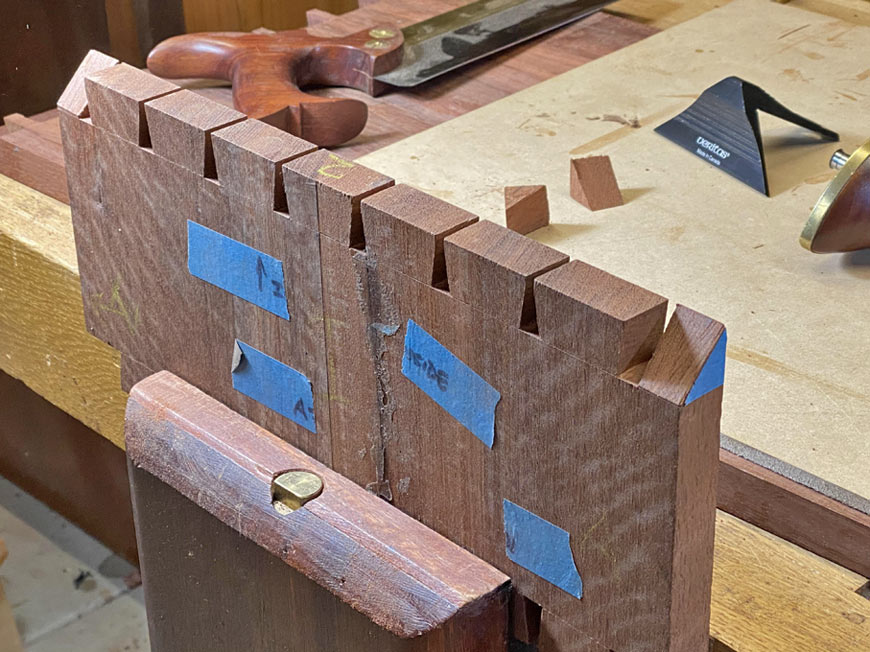

Enough for the case (top/bottom and sides), which will be through dovetailed with mitred corners, the stock for 4 legs (yet to be turned), and rails for the legs (the legs will be staked mortice-and-tenon) and attached with a sliding dovetail.

Regards from Perth

Derek

The build is an entry hall table for a wedding present for a niece. Her choice was this mid century modern piece, which will be the basis for the build. My job is to re-invent it somewhat.

She wants Jarrah, and I have managed to find something spectacular ... a subtle fiddleback (curly) set of boards that will make a book match (as they are only about 9" wide each).

Most imagine that the value of a slider lies with cross-cutting. It certainly is so. However it is the rip using the slider - rather than the rip fence - which is so amazing.

One side of each board was to be ripped on the slider, before being jointed and resawn. Ripping on the slider is such an advantage with life edges. No jigs required. No rip fence to slide against. Just clamp the board on the slider, and run it past the saw blade. The long sliders can complete the rip in one quick pass. It occurred to me that I should take a few photos of ripping to width since the boards are longer than the slider.

Here you can see that it comes up short ...

In actuality, with the blade raised fully, there is a cut of nearly 54" ...

The solution is to use a combination square to register the position of the side of the board at the front, and then slide the board forward and reposition it ...

... and repeat at the rear ...

The result is a pretty good edge, one that is cleaned up on the jointer in 1 or 2 passes, and then ready for resawing ...

This is the glued panel. It is long enough to make a waterfall two sides and top section (still oversize) ...

The following photo shows the lower section at the rear. What I wanted to show is the way boards are stored. Since I shall not get back to this build until next weekend, all boards are stickered and clamped using steel square sections.

The steel sections are inexpensive galvanised mild steel. These are covered in vinyl duct tape to prevent any marks on the wood and ease in removing glue ...

Done for the day ...

Enough for the case (top/bottom and sides), which will be through dovetailed with mitred corners, the stock for 4 legs (yet to be turned), and rails for the legs (the legs will be staked mortice-and-tenon) and attached with a sliding dovetail.

Regards from Perth

Derek